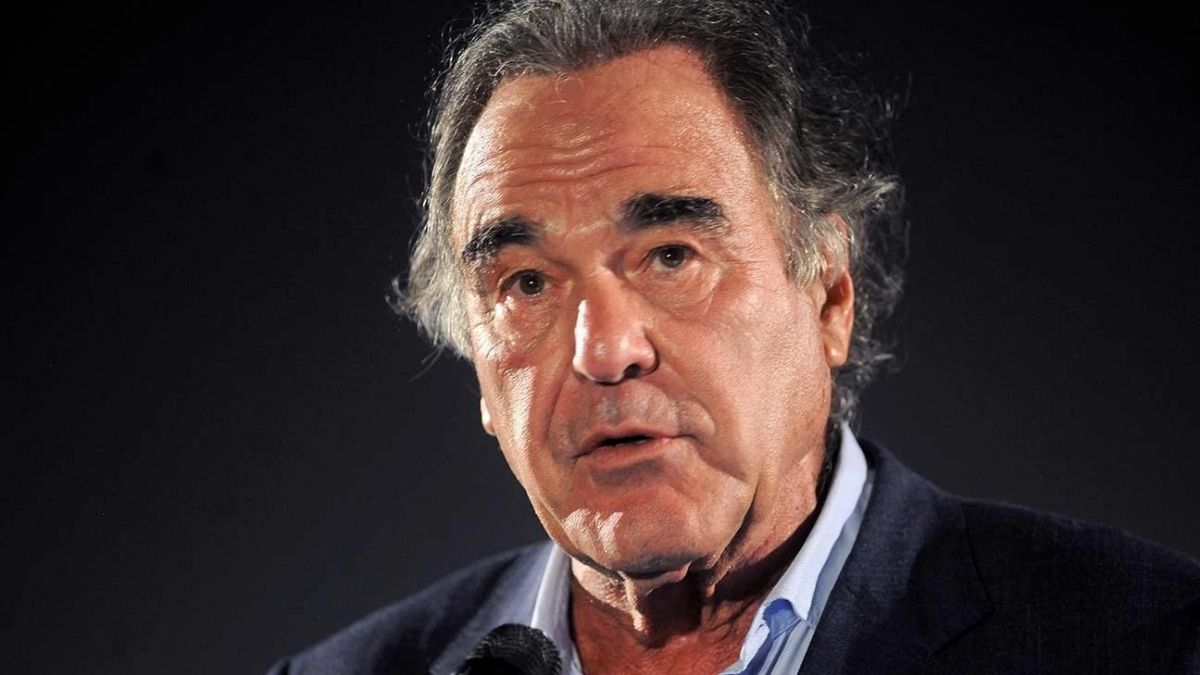

“America has an aggressive gene,” director Oliver Stone tells me. He should know. He’s arguably been his nation’s most entertaining chronicler. Besides, along with American University history professor Peter Kuznick, Stone is working on a comprehensive, multi-part documentary series that alternatively details America’s history, or what he calls, “The Untold History of the United States: essentially everything I can’t say in a movie (a feature film).”

He’s put in over three years on it. As we speak, the film isn’t ready yet (though it would’ve been on air when you read this). No one can deny the film will polarize its audiences, all polemics are meant to. Some of the things he’s said on Mao, even Hitler, often quoted out of context, have perked up ears, occasionally for no reasons at all.

It’s said, if you’re 20 and not a Leftist, you don’t have a heart. If you’re 50 and still a Leftist, you don’t have a head. Stone is 66, enfant terrible still. He swings to the Left, though calls himself “left of centre”. That may be because the Centre itself, across the world, has shifted somewhat to the Right.

It is a brave new world, where a US president steps out of India with promise of new jobs for American citizens, something that would’ve felt cruelly ironic only few years before. When I met him first, Stone himself I suppose was in Mumbai perhaps looking for funds. He attended a film festival sponsored by Anil Ambani’s Reliance, hobnobbing with honchos of an Indian company that seeks a share in Hollywood now.

In a career that pretty much kicked off with Salvador (1986), Stone has made 23 films, most of them controversial, and almost all of them commercial successes. His war movies (Born On The Fourth Of July, Platoon…) have shown America a mirror they’d rather not peer at. “We can acknowledge Vietnam so long as it relates to the memory of American soldiers,” he says.

His political films (JFK, Nixon…) — investigative, conclusive, ruthlessly biting the powers that be — are stuff most nations will not allow to film about themselves. India? For sure not. He believes that’s not true: “Vidhu Vinod Chopra (Bollywood producer-director) told me it’s possible here too. He made Mission Kashmir.” Stone has not seen Mission Kashmir.

It’s only fair that I ask him:

Throughout your career, you’ve been deeply critical of America and its policies. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, Indians love America. One of the reasons we do so is because that country can still produce a potent voice like yours, and within its own mainstream.

Well, I have been critical of my country. But I also share deep love for it. I grew up there. My mother grew up in France; my father literally picked her up from the streets of Paris. Their relationship was product of a World War II encounter. I grew up with a truly migrant mentality, where you don’t take anything for granted. America certainly didn’t have problems of many other countries. We were caught up in the concept or myth of being the last hope for freedom. Upon that myth, I went to Vietnam to realise how painful and horrible (its consequences) were. It’s such mistakes of the past that we rarely remember and have to keep repeating.

I wasn’t to begin with an angry person. I was a conformist in fact. I went to NYU (New York University) to study film. The anger however kept growing within me. It got expressed in the form of, say, Toni Montana (lead character in Brian de Palma’s Scarface that Stone co-wrote). Or Billy Hayes (hero of Alan Parker’s Midnight Express, which was Stone’s screenplay). This articulation was still inchoate.It’s in 1985 when I traveled to Central America, worked with Richard Boyle (co-writer and lead character in Salvador) that my voice found its axis. Even when angry, I remained responsible. (This is around the time) my father asked me, Why don’t I make a film on business and morality (Wall Street).

Being responsible as against rabid of course. Is that one of the reasons you toned down World Trade Centre (2006) completely, given American wounds were still too fresh, the film came out fairly close to the 9/11 attack.

Fear was heightened at the time, we were in the middle of hell, and they (the two lead characters: Nicolas Cage, Michael Pena) were literally buried alive to deal with a situation. Yet they weren’t filled with hatred and vengeance. It’s the family scenes that kept them alive. Family life, even if clichéd, is a crucial, anchoring element in many of my films. With WTC, I didn’t pull my punches. I wasn’t interested in the story of the conspiracy, the jehad… That response (of mine) came later with W (2008), in the national security scene, where I said everything I had to, which sub-consciously put, was for America to get a grip on itself.

A downside of political films is restrictions that perhaps filmmakers face, over things they can say or show. Most directors in India, for instance, can barely imagine a reasonably scathing biopic like W on the early, decadent life of their head of state (George W Bush) while he’s still in office.

I was able to do it because there were already books and literature attacking Bush. I was merely collating and reporting them again, not saying anything new. By 2004, Bush had also lost all benefits of doubt. I took a conscious decision to chart out his early life up till the point he decides to send American troops to Iraq, desperately trying to outmuscle his father’s legacy. He is a loser who fumbles his way to the top. I think barring a couple of wins in basketball, he was completely an incompetent, basket case. It’s a very ‘Voltaire-ian’ story that way.

He was still never willing to believe he ever did anything wrong.

Yes, that is true, remember the bedroom scene (with wife) in W… If Bush did doubt his decisions, he’d have to shoot away his own life.

Surely you’ve been asked this before. Did it surprise you that Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas), someone you’d designed as an indefatigable villain from Wall Street, became the hero of his times? In a way, you were prophetic in 1985 of what stock-market greed could lead America to (in 2008).

The inherent cynicism in it being okay to f*** everybody else, and become successful, may be good for movies. It’s bad for society. There’s something wrong with Americans who love a ruthless bastard like Gordon Gekko. In fact, The Social Network (Mark Zuckerberg) is the new son of Gekko! It’s not a good way to live, the father (Martin Sheen in Wall Street) gives that prophetic advise. An economy that doesn’t produce but makes dollars from dollars is not sustainable. Now we have an America that has suffered a horrific heart attack.

In the new Wall Street (Money Never Sleeps) on the other hand, one of the characters describes a changed world of “Mumbai, Dumbai”.

Yes, Mumbai, Dumbai!

Does this new financial architecture and the region interest you enough to make a film?

India, China, these are fascinating stories. But if I were to make a film on them, they’d have to be documentaries. In the Wall Street of 2008, New York is still the story’s centerpiece. The China story is about huge government deals that someone more familiar with the subject would be better equipped to deal with.

South Of The Border, your last documentary set in South America, is a result of unlimited, rare access to leaders like Raul Castro (Fidel’s brother), Hugo Chavez (Venezuela)… To what extent do you think such “access reporting” affects the objectivity in story-telling. You’re entirely indebted to your subjects. I know weak-kneed journalists face this a lot in their jobs.

You mean the Bob Woodward phenomenon, where one gains access to a story, but is expected to play ball. This would be true (for journalism). In Looking For Fidel, for instance, there were questions for Castro given to me by HBO that were expressly hostile. There were things the American establishment wanted to hear from Castro, and I was supposed to grill him. He even got angry with me, was exhausted by the end of it, but was still not rude or impolite. A film that way is different. The footage remains uninterrupted. You’re merely letting the subjects speak for themselves, that’s all.