So easy to fall for Feluda!

Book review by Mayank Shekhar

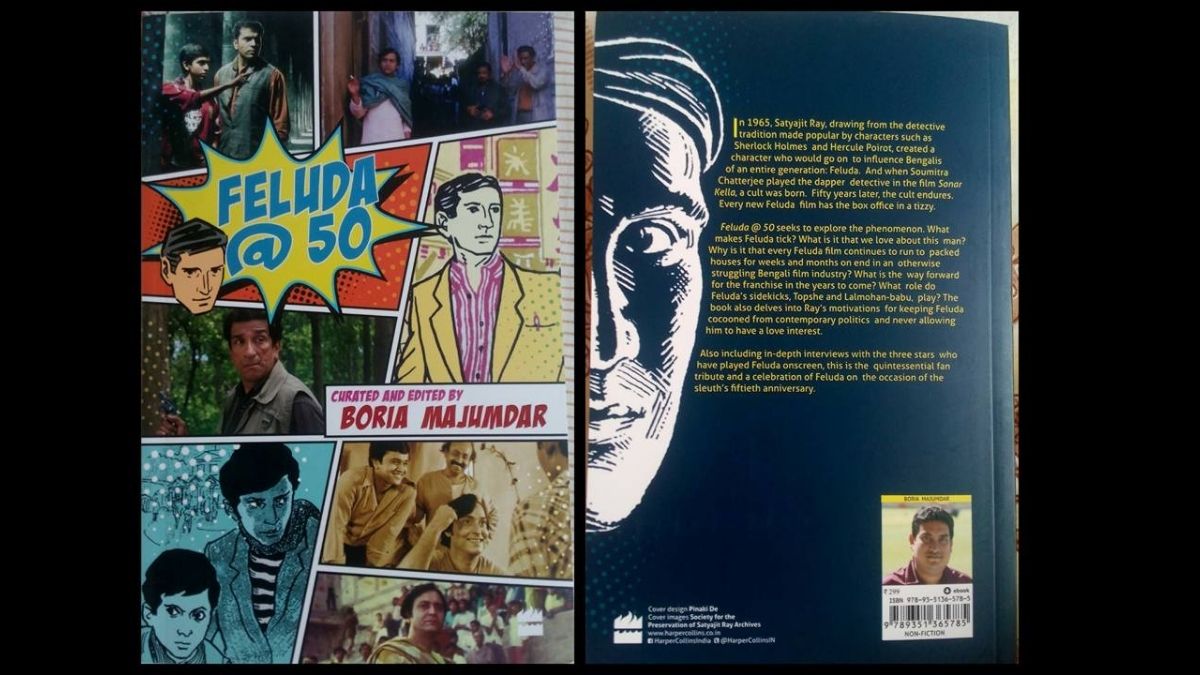

Feluda@50

Edited by Boria Majumdar

Published by Harper Collins

Nostalgia is a comforting but insurmountable exaggeration. The beauty of Bengal, or Kolkata, continues to be sustained best by the intense championing of its icons—from Rabi Thakur to the rosogulla, football clubs to Flury’s—mostly by bi-cultural Bengalis across the globe.

The ones I meet in present day Kolkata on the other hand usually sound despondent about most things. Because I guess, they live in Bengal. Bengal does not reside in their imagination alone.

It is with slight trepidation therefore that I began reading Feluda@50, ‘curated and edited by Boria Majumdar’. Especially as Majumdar starts off reasoning out his own fondness, and of Bengalis in general, for Satyajit Ray’s super-sleuth Feluda. The argument being that the famous resident of Rajani Sen Street was actually superior or generally more sorted than other fictional detectives we’ve known or loved—Sherlock Holmes (too many quirks, has mood swings), Hercule Poirot (snob), Inspector Morse (alcoholic), Kurt Wallander (work-obsessed)… Oh, come off it.

Through essays by hardcore fans of Feluda and Q&As with actors who’ve played him in films, the book celebrates 50 years of the fictive universe created by Ray, centred on the private investigator Prodosh C Mitter (or Felu), his very young assistant and cousin Topshe, his sidekick or co-hero Jatayu, and the colourful arch enemies Maganlal Meghraj, Mandar Bose, Dr Hazra, and others.

Those early unnecessary comparisons to international sleuths apart, my essential fears about the book remain wholly unfounded. This is fan non-fiction, yes. And hence wholly devoid of critique. But there is healthy mix of nostalgia and broad connections with current Bengal, or Kolkata, at any rate. This is because half a century later Feluda occupies a rather enviably unique position in Bengal still.

Ray had of course written the series mainly to appeal to teenaged audiences. The crimes inevitably involved thefts and forgery, nothing outlandishly macabre. What stood out was also the absence of any reference to sex. Feluda had no love-interest. There were hardly any female characters in the stories. So much so that actor Sabyasachi Chakrabarty, who grew up obsessed with Feluda, modeling his life on him, stayed totally off women in his teenage years.

Chakrabarty has played Feluda six times on the big screen, five times on television—directed by Ray’s son Sandip who’s made it his life’s mission to further Feluda’s (or his family’s) legacy. Besides, Chakrabarty has voiced Feluda on radio for three years, and continues to play him on stage.

So at one end you have a literary character that kids in Bengal across generations, particularly in the late ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, devoured almost as a rite of passage. The essays in this book, chiefly by writers Indrajit Hazra and Sovan Tarafdar, warmly place Feluda alongside their other childhood pop-lit icons Bantul, Ghanada, Tenida etc. Nostalgia is complete.

On the other end, you sense Feluda hitting Malcolm Gladwell’s ‘tipping point’ of sorts with Sandip’s Doctor Munshir Diary in 2000. Sandip has in fact been delivering a Durga Puja / Christmas Feluda release to packed halls in Bengal over the past decade and half since.

This timeless interest in Feluda is not so hard to fathom. Feluda was originally imagined as a character living almost in a kinda time warp. When Ray wrote him in 1965, he completely cocooned his sleuth away from the socio-political upheaval in Bengal at the time. Feluda and the crimes existing in a vacuum before him now, stay as good as Feluda’s adventures then. Byomkesh Bakshi would necessitate a ‘period feel’ on screen instead.

It reminds me of Ray’s fascinating 1982 interview with Shyam Benegal (available on YouTube). While answering incisive questions on preferred lenses, camera angles or colour tones, Ray at some point pithily states that much beyond technique, what he’s anxious about is to communicate. With Feluda, he knew his massive young readership, and he stuck to a very uncluttered and simple narrative.

This brings us to the relationship between Ray, or Manikda, and Feluda himself. Many in this book and otherwise argue that the ‘Renaissance Man’ Ray (artist, writer, director, composer) had modeled his tall, polite, morally upright private detective, blessed with love for trivia, travel, and even typefaces, on himself.

The connections between Manikda and Feluda appear quite accurate actually. Something he didn’t quite deny. It is befitting tribute then that while the world can’t still get over Ray’s Apu Trilogy, and cinephiles in France probably still swear by Agantuk, he is still most loved in Bengal for Feluda.

Sure he’s been around for half a century now. Sandip has remarkably guarded the series in its original intent or avatar. Where does that leave Feluda looking ahead though? Should he technologically or socially upgrade his asexual self—the way the BBC did with Benedict Cumberbatch to reinvent Holmes for an altogether another new audience?

Not that one’s asking to make a falooda out of him. But purists in Bengal, particularly the actors (Chakrabarty, and Abir Chatterjee) featured in the book, vehemently disagree. They fear losing out on the charm of Feluda holding the Charminar cigarette, or picking up fresh chanachur from New Market.

Is that why Feluda’s immeasurable appeal didn’t quite spread beyond Bengal? Can’t be. All universal stories are specific first. I suspect there was a missed opportunity in that regard, when Shashi Kapoor played Feluda in the tele-series Joto Kando Kathmandute. Soumitro Chatterjee (the ‘real’ Feluda from Ray’s Sonar Kella and Joi Baba Felunath) rightly believes Kapoor was just too old for the agile, young Bengali detective’s role.

So be it. It’s unfortunate still. And it cannot be so hard to undo. While Bengal would like to claim Ray as wholly their own, which is fair, Ray rightly saw himself as an artiste of the world. As should his creation. As for this collection, I think it deserves space in Feluda’s very own personal ‘Google/Wikipedia’ Sidhu Jyatha’s library. And every Feluda fan-boy/girl’s as well. There’s much to find and love about Feluda, always.

Mayank Shekhar’s book NAME PLACE ANIMAL THING, on desis and pop-culture, is available online and at leading bookstores

* Edited version of the above piece was first published in India Today magazine