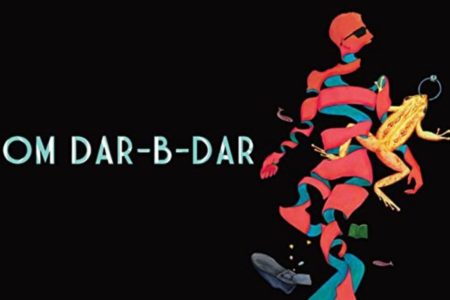

Like everyone else, I wank off in the privacy of home, always behind closed doors. Some majestically do it in full public view by making a film. Om Dar-B-Dadar is one such piece of visual masturbation.

Outlining its plot is impossible, so I take the help of a review on SeventhArt.com that best explains what the film is about. Rap this like ‘We didn’t start the fire’, if you like: “Horoscope. Dead frog. Cloudy sky. Radio show. Terrorist tadpole. Caste-based reservation. Bicycle. Mt. Everest. Women’s lib. Communism. Sleeveless blouse. Yuri Gagarin. Miniature book. Nitrogen fixation. Computer. Man on moon. Biology class. Hema Malini. Turtle. Typewriter. Text inside nose. Googly. James Bond. Severed tongue. Shoes outside temple. Gandhi. Hopping currency. Goggles. Helium breath. Diamonds inside frogs. God. Promise toothpaste. Nehru. Aviation centres. Potassium cyanide….” Another line from this review of the film, ‘The great Indian LSD trip’, adorned its poster in its first theatrical release this month, about 25 years after the film was made.

While the disjointed film defies description, it has enough genres heaped on to it, recurrent ones being ‘post-modern’ and ‘avant garde’. Now I’m no art academic. But I suspect theorists will be able to find in the film traces of Dadaism, which was a short-lived anti-rational, anti-art movement (1916-23) in Europe. This is when artists felt that a world so much at war deserved no formal art whatsoever. Marcel Duchamp’s mustachioed Mona Lisa and a public urinal hung upside down are popular relics of that movement that attacked every existing –ism of any kind. These works were designed to offend sensibilities. Kamal Swaroop’s Om Dar-B-Dar seems like a response to Indian cinema’s serious, self-conscious art-house movies of the ‘70s and ‘80s that stated such obvious truths about the human condition.

The film is instantly surreal, making it an expression of subconscious thoughts or dreams. Dali was probably the dada of that genre, and Bunuel possibly the baap. Together they made a film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) in 1929, financed by Bunuel’s mom, which gave the filmmakers an official place among artists of the Surrealist movement. Otherwise, film is considered too expensive a medium to experiment with such artistic anarchy.

Government-run NFDC had produced Om Dar-B-Dar. Swaroop had strong credentials. He had graduated in direction from the FTII, Pune. Along with Mani Kaul, Saeed Akhtar Mirza and K Hariharan, he had directed Ghasiram Kotwal (1976), written by Vijay Tendulkar. He had assisted Richard Attenborough on Gandhi (1982). For his directorial debut, he approached NFDC with a completely linear synopsis of his script, which is clearly not how he eventually filmed it. The producers must have been disapprovingly shocked by the outcome. Om Dar-B-Dar didn’t get a release anyway. The film went straight to the cans, instead of the Cannes, though it did premiere at Berlin. It didn’t make it to the government’s Indian Panaroma section that ensures screenings at state sponsored festivals. Miraculously enough, it picked up Best Film (Critics) prize at the Filmfare Awards, which was then more than merely a television event.

A thoroughly confused Censor Board at the time didn’t grant the film a viewing certificate. They believed that while they couldn’t make head or tail of the movie, there must be subliminal, subversive messages being transmitted through it that may adversely affect an unsuspecting public.

Almost like illicit cargo, a spare VHS tape from the one that Swaroop had cut for the censors found its way to an arts camp in Kasauli, thanks to art historian Ashish Rajadhyaksha. This is where the film was perceived as being close to artist Bhupen Khakhar’s works. It found favour among the art frat. The likes of Manjeet Bawa, Tyeb Mehta, Vivan Sundaram, Akbar Padamsee, I am told, would watch it over and over again. It helped Om Dar-B-Dar establish artistic cred. Copies of the VHS got into circulation. The print was viewed as staple diet by all subsequent batches of the FTII. The gospel subtly spread among young filmmakers with artistic aspirations.

The brass band section in the song ‘Emotional atyachar’ from Anurag Kashyap’s Dev.D (2009) is evidently homage to the Om Dar-B-Dar track ‘Meri jaan AAA’, which is also the song Natha’s son hums when his father disappears, in Anusha Rizvi’s Aamir Khan production Peepli Live (2010). My favourite number in the film is ‘Bablu Babylon se’. This is the song that helps two lovers meet in the movie. Both of them had been repeatedly placing a request for the same track over the years on Vividh Bharati— the boy Jagdish, from Jhumri Talaiya, and the girl Gayatri, from a fictional Rajasthani town, where the film is set. The girl is the protagonist Om’s elder sister. On the face of it, the film, in chaste Sanskritised Hindi, is a hallucinatory journey from adolescence to late teenage, of young Om, who is an astrologer’s son. If you sit down to follow that story, good chances are you’ll lose your mind. Deliberately hammy actors add to the humour.

Swaroop says he took about three years to figure out a script, spending most of that time discarding any aspect in it that seemed like a film. He argues that if you merely remove sex and violence from a movie—it stops looking like one.

There is a toy gun in Om Dar-B-Dar for violence. And a brief direct reference to sex when Gayatri asks Jagdish to sleep with him—drawstrings of the boy’s boxer shorts refuse to come off, her hyperventilating father spins back and forth in his cycle before collapsing outside the house. Swaroop says he took that ‘naara scene’ directly from Manohar Shyam Joshi’s novel Kasap. Rajat Kapoor referenced it in his film Mixed Doubles (2006). The last time I heard Rose Mary Marlowe, a pulp author’s name in Om Dar-B-Dar, was in a recent farty sex-com Grand Masti (2013).

For his own references, Swaroop says he drew heavily from a free-spirited Maithili-Hindi-Bengali writer Rajkamal Chaudhary from Mahisi in north Bihar. Chaudhary’s writings effortlessly merged ‘American pop literature with Indian literary traditions, delving strongly in self-exorcism and black magic.’ Chaudhary is often credited for one of the earliest references to lesbianism in a Hindi novel, Machhli Mari Hui, which is also one of the books that Swaroop claims primarily inspired Om Dar-B-Dar. Chaudhary died of syphilis at 38 in 1967.

Swaroop, 61, hasn’t made a feature since Om Dar-B-Dar. I first began to hear about the film in the late 2000s. A screening at Mumbai’s relatively underground festival Experimenta in 2005 had apparently led to a belated buzz around it. The psychotropic substance, from print to VHS, had begun to proliferate itself like frogs in a pool—key characters of Om Dar-B-Dar—as the film went digital on Torrent. Internauts began to blog about their first Indian surreal film experience. These were usually young cinephiles whose eyes were still open to viewing movies beyond a straight and simple storytelling medium. Much like the absurdities of life, the film makes no obvious sense. It is not meant to. Some prominent critics began to pester NFDC to digitally restore the film. They could recover some of the cost with a theatrical release, even if from a single show in a private screen, PVR, across major Indian cities. But that’s immaterial.

Internet makes it hard to predict what will survive public memory anymore. The web, chiefly YouTube, had already liberated Om Dar-D-Bar’s scenes, satires, codes, songs and non sequitur dialogue from the film, turning them into individual vignettes to be multiply interpreted or enjoyed for their own worth: ‘Aatankari tadpoles’, ‘Rana Tigrina’, ‘Om fights with bicycle’, ‘Out of course’, ‘Letter to Nehru’, ‘Aa kood, isme khazana chhipa hai’…

Viewing the whole thing without any warning, I wouldn’t be surprised if you turn around, super frustrated, to ask, “Is this even a film?” Yes it is. Or maybe it’s not.