Since this was quoted to me, I don’t recall the original author of the ‘gubbara principle’ of interviewing. Wherein, the art of scoring a great journalistic interview lies in treating the interviewer like a balloon—pumping him up with immense praise, over at least three-quarters of the conversation. By which time, he’s totally on your side.

At some point, with no space left for any more air and flattery, you smartly/casually prick that excessively bloated balloon, finishing the chat off with the most uncomfortable/controversial questions, when he least expects them. He has no option, but to comply.

As a rare (if not the only) Indian journalist who, for about three decades, has made a living, almost entirely from interviewing public figures on national television, Karan Thapar clearly follows the opposite of the ‘gubbara principle’—going for the kill, right from the first shot.

This explains the two interviews of politicians he’s best known/revered for. The irony is that through those two very interviews, at least consciously, we learnt nothing about the interviewees themselves. One, being Narendra Modi (as Gujarat CM), who walked out in three minutes flat. The other, J Jayalalitha (as Tamil Nadu CM), who’d so had it, it’s likely she would’ve revealed anything anyway.

Did they both make for great television? Absolutely. To get that, you only have to acknowledge current-affairs’ anchor Thapar’s art of conversation as being hinged not so much on interviews—question-answer, often staid, even staged—but deeply entertaining duels, in the spirit of a cross-examination, at a British parliamentary-style debate, where participants (usually two on either side of the motion) are dressed impressively in formal suits, rebuttals are delivered with flourish, and debates conducted, naturally, with less interest in understating, or even granting an argument—as much as in demolishing it. You’re in it, to win it.

Applied to a one-on-one format, this would mean taking a temporarily adversarial position, backed by persistence, right from the point of bringing the guest to the table (countless calls), and metaphorically banging his head on it, before it’s all done. You shake hands then. And hope to meet another day.

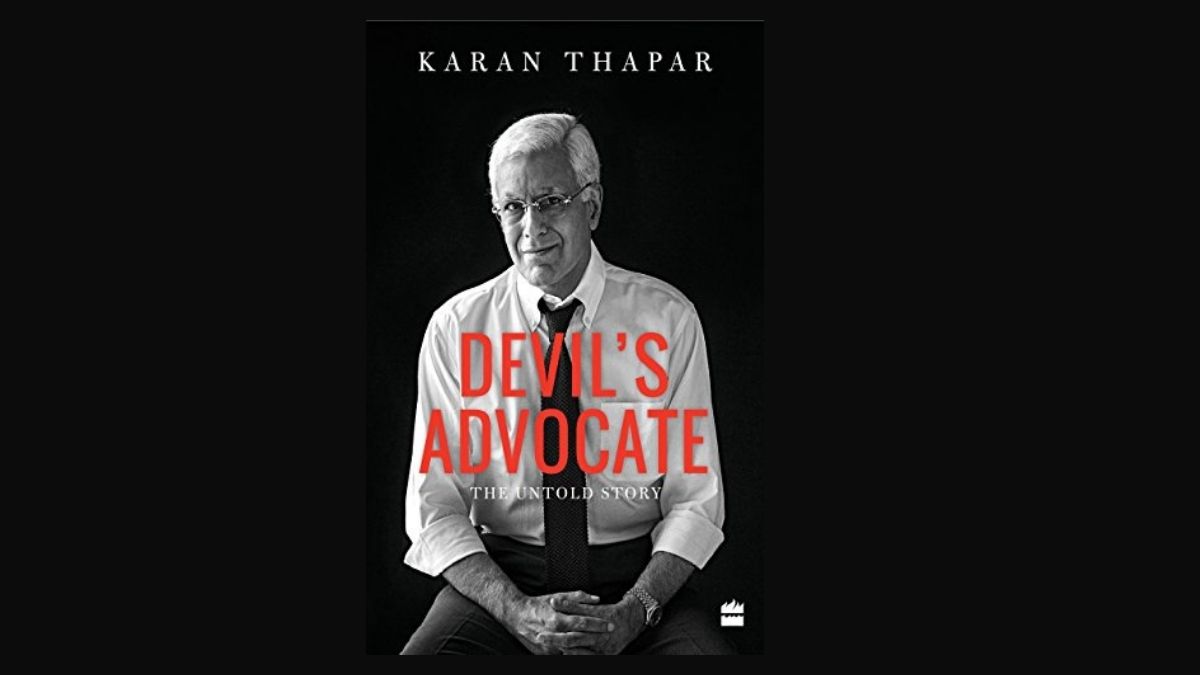

Much of where Anglophile Thapar’s style comes from is present in his memoir, Devil’s Advocate: The Untold Story, which he literally dictated to his secretary—perhaps like Bertie Wooster to Jeeves? Son of ex Army chief, Thapar was president of Cambridge Union (top debating society).

An early lessons he learnt while working with Channel 4 was from its programming head, John Birt, “who famously believed there were only four answers to any question an interviewer might ask—yes, no, don’t know, and won’t tell. The job of the interviewer was to collapse the last two into the first two.”

Having lived in the two deeply political capitals, New Delhi and London, Thapar’s book is understandably littered with several name-droppings—he was Benazir Bhutto’s BFF, close to Aung San Suu Kyi. Growing up, he hung out with the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s kids, Sanjay and Rajiv. The latter, as PM, got him a job, with an IAS Secretary-level rank, in Doordarshan, and thereafter with the Hindustan Times’ television company.

This level of proximity between journalists and powers-that-be, is often derided as ‘Lutyens’ class’ in political circles, and of late, on social media. It’s fashionable to treat media (misnomer for press), which is only a plural for medium, as a monolith—for it primarily operates on access, or patronage.

This is a popular political tool to diminish a voice. Within the circle itself, you only have to watch Thapar’s contemporary, Madhu Trehan, interview him (twice), supposedly in his style, on Newslaundry, to get a sense of how much everyone pulls each other down like bickering babies anyway, making Twitter trolls seem tepid in comparison.

Either way, the act of interviewing, at least for that moment, places on the interviewer a certain amount of power (given every word has an audience) that he can either exercise to gently draw out his subject—by being curious on the audience’s behalf—or push them into a corner, to score a point.

The best interviewer, according to Indian television’s top fire-brand Arnab Goswami, as he told me once, is James Lipton (who conducts In The Actor’s Studio, with Hollywood stars). Each episode is a compelling profile.

Thapar’s ‘Devil’s Advocate’ works best only with politicians, since other public figures (from pop-culture in particular) owe you nothing. You didn’t like her movie/music—you’re free to not hear/watch it. Unsurprisingly, Thapar says his toughest interview was with the reticent AR Rahman, although that chat was quite genial; the warmth, if you may, was missing. Maybe that’s what he’s incapable of.

Still, it can be a tricky thing to publicly converse with those who aren’t, strictly speaking, social equals—I say that, since the audience is interested in the interviewee, not so much the interviewer. There is also an understandable, even inevitable, possibility of getting star-struck.

I find Thapar equally star-struck before the camera. Only that he’s convinced he’s the star! This could annoy some (viewers, let alone the subject). Frankly, I’ll take that over the perennially servile, or the selectively ferocious, any day.