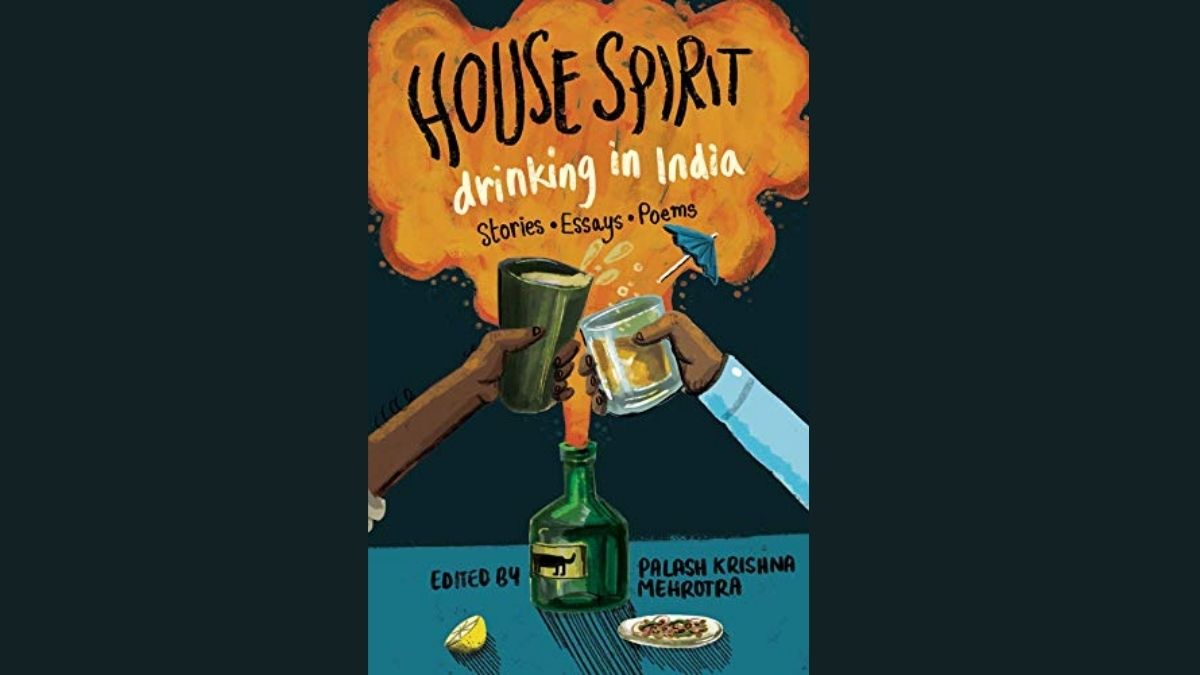

House Spirit: Drinking in India

Edited by Palash Krishna Mehrotra

Publisher: Speaking Tree

Pages: 276 / Price: Rs. 399

Like booze on a ‘dry day’ or after bar hours, you could always do with a book such as this—maybe even a few more. Here’s why. Soon as I sit down to think about to fill this page up with, I see a tweet from @fact, my favourite Twitter trivia handle. “Alcohol,” it says, “is older than the Great Pyramid at Giza, the Roman Coliseum, Machu Pichu, the Taj Mahal, and the Great Wall of China, combined.”

Now just think about how ancient is the much-approved act of drinking historically—or in your own adult life, if you’ve been a drinker through most of it. The booze then will seem like man’s most under-valued friend.

We incessantly recall (or try hard to recall) extraordinary evenings spent in its company. We share details of the said nights—what we said, heard, did, or where we landed up finally (“no, really?”). And yet that bottle on the table being the most important friend that night, under whose overpowering influence we always were, remains the elephant in the room. We rarely spend much time discussing it directly at length. It’s always about the evening, never the catalyst.

Palash Krishna Mehrotra’s wonderfully introduced, curated anthology on drinking in India, clearly aims to redress that wrong, through an eclectically chosen set of fine short stories (by writers such as Gautam Bhatia, Siddharth Chaudhury, Aditya Sinha, Jeet Thayil, Anjum Hasan, Anup Kutty); poems by Mahohar Shetty, Vijay Nambisan; and essays by Pavankumar Jain, Indrajit Hazra, Samanth Subrahmaniam, Abhinav Kumar, Adil Jussawala, among others.

The collection mainly looks at why we drink what we drink. And what it does to us—depending on how we drink it, or even who we are. I guess we sort of know why we drink, or think we do.

As a veteran stockbroker tells writer Manohar Shetty, who manages a vegetarian bar by the Bombay Stock Exchange: “Both ways you win: if we make a windfall we come here to celebrate; if we lose we come here to drown our sorrows.” Besides depression and happiness, we perhaps drink to every other shade of human emotion in between—but most likely, because we are plainly bored. And the booze helps speed up time.

Before you know it, as in the case of Kanika Gahlaut, who’s no more a drinker at 40, “nights turn into decades.” Sometimes even reaching a point when the booze becomes your only friend—everyone else, the family included, having turned against you, tricking you into rehab, pocketing away everything you’ve got, maybe for your own good, but mostly for theirs—or so is Vijay Nambisan’s terrifying account of supposed alcoholics being picked up like stray dogs into municipality vans.

Many others similarly knock themselves over, making life with all its hardships partly endurable, at Kerala’s toddy shops—“shaaap”, pronounced sharp, without the burr—or on country liquor, cheap nips, quarter bottle shots, or other similar intoxicants.

But that’s not the point. We’re aware of alcohol’s rougher side—addiction, loneliness, low self-esteem, hangover…. It is in the interest of society to exaggerate the effect of booze to collectively guard against its possible excesses. That’s I guess the reason Sidharth Bhatia finds the depiction of drinking in Bollywood oscillating only between tragedy (Devdas) and comedy (Johnnie Walker)—never simply as something that a third of India’s population (statistic quoted by Sandip Roy) casually consumes, chiefly to unwind.

Of course booze does different things to different people. “There are (various) types of drinkers,” according to Gahlaut. “The binge drinkers. They let go. And the next morning, they are in control again.

“The sliding drinkers—you see them fall slowly and steadily into the arms of seductive booze, unable to come up again, the intellect slowly wasting away.

“The hangers on: drinking for them is not the purpose. They feed off the energy of other drinkers, going with the flow.” To get back to @fact (okay I need to get off Twitter now): “There are four kinds of drunks: Nice drunks; mean drunks; introverts that turn extroverted drunks; and drunks who retain mental faculties.”

Be that as it may, the booze serves as social lubricant. It helps some (men and women alike) lose their inhibitions enough to swiftly make an attempt at getting laid. Most Indian men are rather sloppy at this. This is the reason it is for the better that there are only men at small-town bars in India—as Mehrotra’s short story ‘Dancing With Men’, set in Dehradun, describes it. The focus doesn’t waver from alcohol. And among a group of men, otherwise unused to drinking with female friends, the alcohol has the instant effect of deepening male bonds, or even dirty dancing together, as it were.

For most, like me, in a place like Bombay, where the city already saps you through the day, drinking equals going out. The place is central to the story. As is the company of course. But much less so. The alcohol anyway takes care of social awkwardness, organically turning strangers into buddies. The neighbourhood bar helps you witness better versions of the people you share a claustrophobic metropolis with—they look less guarded, better dressed, and mostly very friendly. Does any of this fuel creativity? Probably not. Does it shoot up the quality of your social life? I’m not sure. But it inevitably makes for a great evening. What could possibly be wrong with that?

Where you are going, for the most part, therefore, becomes almost as important as what you drink. If I was in Delhi, 4S in Defence Colony, as per Jairaj Singh’s essay, is the sort of place I might find myself in—unpretentious crowd; familial vibe; regulars you can chat up with and forget their names each time you meet them; and waiters you always wish to know better. But with such places, boredom inevitably sets in. If you merely seek the familiar, why not just stay at home? On occasion, I’d much rather check out the Deluxe Bar on CD Road in Bangalore, from Zac O’Yeah’s short story ‘Mr Majestic! The Tout of Bengaluru’.

Speaking of which, Shanti Devi, the 89-year-old bootlegger at a house bar in Sansi Colony in Majnu Ka Tila in north Delhi, from Arunabh Saikia’s non-fiction piece ‘ The Bootlegger and the Bandicoot’, sounds like fascinating company. As does Mohan Bhaiji from Hardiwar, from Mayank Tewari’s short story ‘Mohan Bhaiji’.

*****

There’s an inherent class-system and snobbery embedded into alcohol, given what we drink, or rather where we drink it. Maybe because distilled booze—unlike say bhang, or toddy, or hash, or marijuana—also has strong colonial associations. In his imperialist history of drinking in Calcutta, Sumanta Bannerjee beautifully captures the varying drinking scene or cultures in the White Town and the Black Town of the former capital of British India. Of course everything about Calcutta is what it used to be. Still, this distinction is no different from the present Park Street and the hooch dens in the city’s underbelly. Or even further, between Taj Bengal (new rich), gymkhanas (old rich), and Trinka or Olypub (new drinkers).

Bhaichand Patel in his essay admits he gave up drinking Old Monk, because with time he could afford better—Old Monk, inarguably being India’s most loved rum, a college favourite, if not the national drink. Its owners, Mohan Meakin, have been unable to arrest decline in Old Monk sales since India liberalized its economy, because fancier alternatives—Bacardi, and Vodka based cocktails, for one—came to be seen as uber cool among the urban young.

Only some of these classifications are class-oriented though. Up north at a house party in Chandigarh, the one time I asked for a beer (which is what I normally binge on), the host instructed his waiter to bring it to me with a nipple. You don’t ask for anything but a whisky in Chandigarh. Ideally scotch. The Indian whisky, made from molasses, isn’t grain-based, and therefore another form of rum—not whisky. Manohar Shetty feels similarly about beer: “I’ve never fathomed how people can get high on beer or wine—whatever the vintage or ‘bouquet’. To me they are poor substitutes for hard liquor.”

For Sandip Roy, “The rites of adulthood, or manhood, were pretty clearly marked in alcohol. Beer in high school. Rum and coke (or rather Thums Up) in college. And finally whisky. Vodka—what was that? Gin—that’s what ladies sipped at Calcutta Club. Wine was vinegar.”

I don’t like arguing over drinks. So we’ll leave it at that. But how much should you drink? This, to me, is the toughest call. You feel for Henry Derozio when he writes in his 1824 essay ‘On Drunkenness’: “Whilst they are gay, I am somber. And by the time I’m beginning to get into spirits, they are all under the table. Amiable readers, sympathise in my sorrows! I stand alone in the world. Like Godwin’s St Leon, there is a gulf between me and my species.” Good drinkers will identify with the Godwin dilemma.

Drinking can be at times too much of a good thing. What does it say about those who can while away hours doing it, I don’t know. But as measure of personality and for its sex analogy, I tend to agree with DH Lawrence, whom teetotaler Arindam Chaudhuri is gracious enough to quote in his piece ‘Some Pathologies’: “No, I don’t drink because I feel no craving for drink. This is seen by the people I encounter socially not only to be inexplicable but suspect. For, to deliberately reject pleasure is sinister. As DH Lawrence said of ‘people who are genuinely repelled by the simplest and most natural stirring of sexual feeling… they nearly always enjoy some unsimple and unnatural form of sex excitement, secretly.”

Seriously, no knock on teetotalers, but I have problems trusting a non-drinker. As Khushwant Singh once famously told LK Advani, “You don’t drink. You don’t smoke. You don’t womanise. You must be a dangerous man.”

For all its vice-like grip, drinking has probably brought more instant, unconditional happiness to humans—especially when they’re strangers to each other—than any other social virtue I know. We celebrate with it. But never celebrate it enough, for its own worth. Mehrotra’s anthology, which like all anthologies should be savoured in bits and parts, is great start. I’m only too happy to wait for the next round.

Disclosure: I have my own self-explanatorily titled piece ‘Booze, Bollywood, Bombay & I’ in the anthology, which so far as a review is concerned, must count for the opposite of a ‘conflict of interest’. Quality wise, you tend to compare your own stuff with the others’. This book then might even be better than I’m making it out to be!